By ASHLEY GARRETT

Published in Painting is Dead Nov. 20th, 2014.

Lisa Sanditz spray painting outside her studio in Tivoli, NY. Photo by Tim Davis, courtesy the artist.

AG: When we were scheduling this interview you said you were back and forth between the city and upstate, and that you have your studio there. What do you like about working upstate?

LS: My studio is behind my house in Tivoli, NY. I like walking outside and going right to the studio. When I’m at work in the city, there are so many things that might be happening between my apartment and getting to the studio, I’m always kind of rattled by the time I get there, which I know is a very normal New York experience – passing through many different people and situations. So this is more focused. The studio is not that big actually, but here I get to look at leaves and chipmunks.

AG: In some of your other interviews you’ve told stories behind each painting – if there’s a legend or myth that inspired the work, like the one with the broken heart in the creek, and also with the black balls in the lake – what role does storytelling play in your work? Do you feel that it enriches the paintings when you tell the stories? Do you think the paintings need the stories?

LS: I don’t have any control over how people read them. So whatever a person’s response to it is their response to it. And anybody’s response to any art is informed by that person’s experience, so if I’m making a painting about a place and that painting is shown in that location, then those people are inclined to know what it is. The painting with the black balls in it, which is the Silverlake Reservoir in LA, I showed it in my studio in upstate NY and people had no idea what it was, they just thought it was this intense, overwhelming strange disruption in the landscape, which is what I’m thinking about a lot in terms of sites that I’m painting. But when I showed it in LA, 75% of the people I talked to said they knew exactly what it was when they walked in. So those viewers bring something totally different to it and it means something different for them. I like both the general and specific reaction. I’m always kind of excited if someone can put together the specific narrative, because I think about that a lot. Also, that’s such a weird location, there’s nothing like it, so why would anyone necessarily know that it’s a reservoir that’s filled with 400,000 black balls - it’s not something as iconic as a Christmas tree farm, for example. But I think a lot about narrative and the input, too. Clearly I like to paint, and draw, so why not just make anything? Whenever I try to do something that’s abstract or a still life, I don’t know what to jump off from. I need a narrative to give me an idea of how to visually enter something or even just keep my interest in it piqued. So the narrative functions both in the backend - my end - and in the output too.

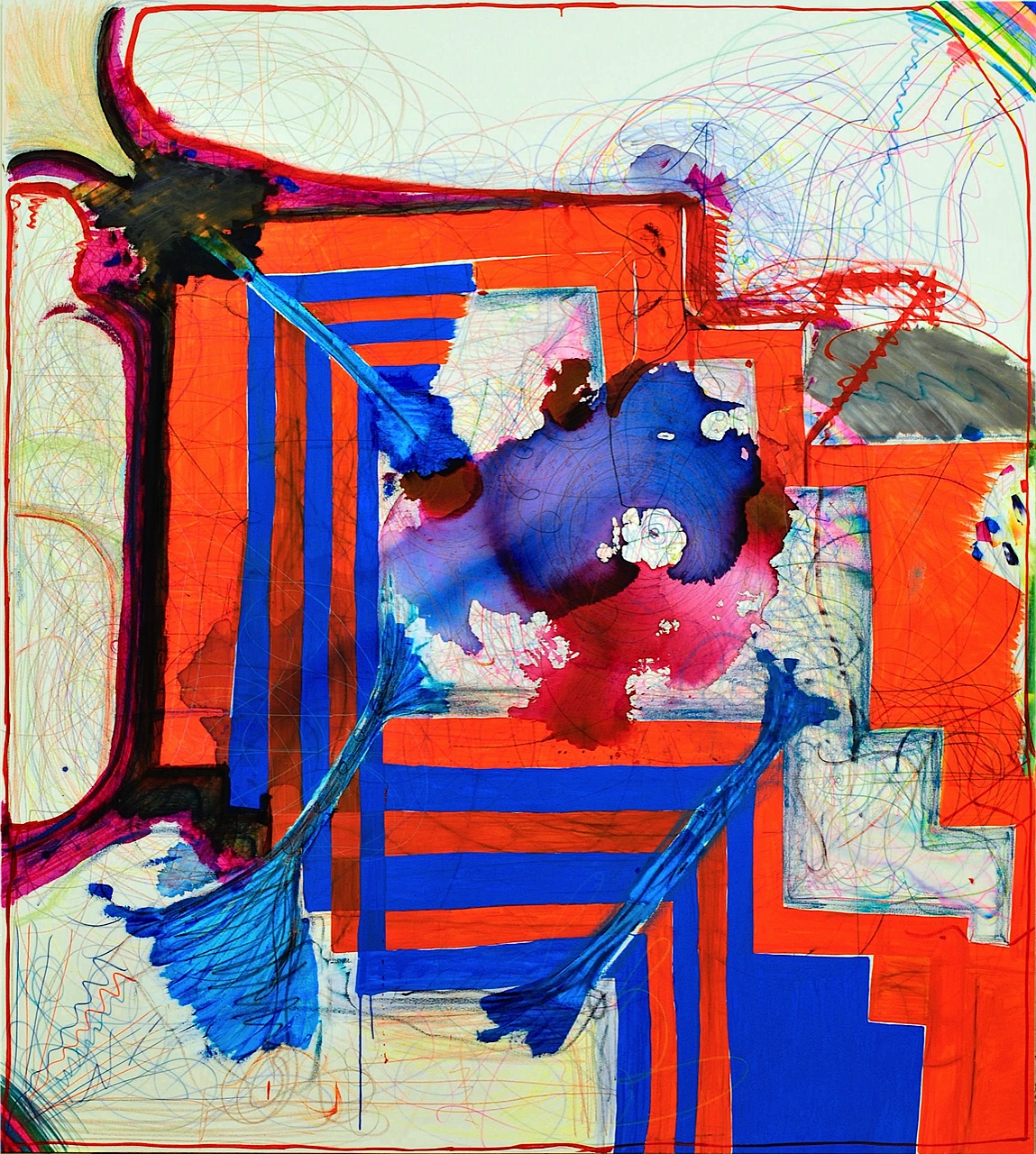

Silverlake Reservoir, 2010, acrylic and oil on canvas, 90 x 70 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

AG: That’s interesting because I feel like there’s a push against narrative in painting. Sometimes people look at work and instantly want to be told the story behind each painting in order for them to even be interested, and that’s always a weird dynamic. I just wonder if it disallows people from having their own experience with the work that’s separate and autonomous, where someone can attach their own story to it. I just never quite know – where is the line, when do you tell? If someone asks, that’s fine, that’s straightforward, but if it’s on the edge or not clear, do you step in and maybe mediate someone’s experience?

LS: Are you ruining or enhancing the person’s experience? I always assume enhancing, because the more information I get about anything, the more I’m just kind of intrigued about it. I remember in grad school at Pratt hearing Thomas Nozkowski coming to talk about his work. He was showing his work and then telling us these specific narratives, or more like experiences rather than narratives, that inspired a painting, and he was showing us a painting of blue and white squares, and he’s giving this detailed story. And it just kind of blew my mind, it didn’t ruin or enhance my experience with the work, I just found it perplexing. It didn’t sway me either way. I wouldn’t have gone there with that painting. That work is much more obtuse, there aren’t the visual indicators of specific things that I put in my paintings. I think people are really interested now too in just the narrative of painting itself. I think that is also more difficult to talk about – it’s easier for me to talk about visiting a cactus farm and what I experienced there than something like: I gessoed the canvas, and then I splashed some acrylic on the background to give like a feel of the atmosphere and tried to pull more representational elements out, trying to relate to the more formal elements in what I see. And I don’t know what artist can talk really well about the narrative process of painting. Obviously narrative is bound to language in a way that painting is not. I don’t know if that’s the limitation or if it’s just the painting magic that’s hard to talk about, or we don’t want to reveal it because we’re magicians, in the same way magicians don’t reveal their tricks.

Power line tree drawings in Lisa Sanditz’s studio in Tivoli, NY. Courtesy the artist.

AG: I think talking about your process is different from talking about the art historical justification for some kind of abstraction. Not that you necessarily have to tell me a story, but let me have the opportunity to tell myself a story with this imagery if I want to. I don’t think we need to hold back from narrative. I don’t think it’s a bad word. I was talking with two other artists this week about narrative and they were both adamant about it not being in their work! I feel like with your work, I could go there if I want to but I also don’t have to necessarily. I feel like I’m given the choice, that you’re interested in that yourself but you’re not forcing me down a particular road.

LS: I think so. More recently I’ve been working on some work that’s still representational but the narrative is broader, maybe less specific and seeing what that means to me or to the viewer too. So I’ve been working on these works on paper of trees that are cut to make room for power lines. They make these weird shapes, sad shapes, over-arching shapes, funny shapes, and it’s one solid narrative throughout. So it’s less about going to a place and then a story or experience happened. As a matter of fact I'm having a show of these tree drawings that are half of trees cut from power lines up here where I live now and the other half are trees cut for power lines around where my parents live in Missouri. In the installation the trees will meet, they’ll be installed in the corner in the middle and they’ll descend like a vanishing point, they'll get smaller and smaller towards the middle and bigger and bigger as they go out.

It certainly has been interesting for me to play around with materials and a narrative that’s a little more specific and doing it over and over again. I tend to work on a painting of a place and a totally different painting simultaneously. So for example a compost pile in upstate New York and then the next painting I work on will be farms I visited in Arizona. So I jump to totally different subjects and formal explorations, so this new work is a more unified narrative from piece to piece. I don’t know if it’s good or not but I’m having fun, so we’ll see. For now, anyway. I’ll let you know how people respond!

Pearl City Study, 2007, acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

AG: Do you travel in particular to look for these weird transitional moments that you’re working with in the landscapes or do you just happen to come across them when you’re traveling personally?

LS: Definitely both. And some are researched in advance and then I’ll go. For example the work in my last show was stimulated by my interest in circular farms that are in the west, in Kansas and Nebraska and Colorado, especially because I was doing a series on farming and how to get around just having giant green rectangles everywhere. So I went to Colorado and hired a plane to fly low over those circular farms, so that was something really specific that I went out there and planned. On the other hand the drawings I’m doing now of trees started around the tree in front of my house – it’s the most half-tree ever, and the half-tree that remains is leaning towards our house. It’s a huge Maple tree that’s half of a Maple tree – at what point does this tree decide that it can’t keep going without it’s other half, and it’s going to fall on the house? So that literally couldn’t be more outside my front door and I’m also noticing that in other locations. And it could also be something I’ve read in the news, the painting of black balls in Los Angeles I read about first in the Times, and I was going out to LA a week later and I knew I was having a show there in a year, so it all fell into place. But I think I definitely get a lot from going places that I wouldn’t otherwise, so that seems to be part of the whole process too. Happenstance, you know.

AG: Do you make the smaller studies and the work on paper alongside the paintings or do they come first? Where do they figure in to your process?

LS: Sometimes I make them on location, so again, that LA painting I painted for like three or four days – the landscape was flat, it was hard to get a good vantage point, so I painted just with watercolor and paper. And then I also sometimes work on the studies when I’m trying to figure out how to resolve something, like in the last show I had at CRG I had this painting Crop Duster, which had the red, white and blue spray paint on it, and it took a while to figure out how to resolve the painting knowing that the spray paint would be the last thing on the painting and all in one shot. I was trying to figure that out on a more modest scale before I did it at 4 x 6 feet. Small failure to prevent big failure, big failure happens anyway. So I work on them in advance, in tandem, and on the go.

AG: The way you’re handling watercolor and the acrylic on paper looks very different, the touch is sensitive and fluid, and the finished acrylic and/or acrylic with oil painting has a very different look to it - there’s a quality of a kind of “grossness” in the handling of the paint in the bigger work, in the big heavy drips and some of the clunky shapes, the dirty colors, heavy textures – does the mark-making match the subject of the industrial and commercial landscape that you’re depicting?

Spray Tree, 2014, spray paint, colored pencil, marker and gouache on paper, 38 x 50 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

LS: I think both, I think it’s part of the work and then part of the material limitation and generosity. I’ve been working on paper mostly for the last few months, and the way that it absorbs the wet material and the dry material feels so rich and present, while working on canvas is like painting on the surface of the moon! I’m not someone who gessoes the canvas 20 times, but I do it six or eight times, and the paint still gets sucked in and it doesn’t record marks in the way some of the other mediums do. Watercolor shows every single drop of the pigment. So I like both for what they can and cannot give you. And sometimes it’s a little bit of an attack and the painting gets kind of fucked up and sometimes that’s good and sometimes it goes overboard. But I definitely think about finding some of the glory and the grossness of these sites, and then I definitely want to get that into the paintings.

AG: In looking at the work online, I really thought your paintings were all oil but it looks like you work primarily with acrylic and occasionally use oil, and then I was watching your interview that you did a little while back with Gorky’s Granddaughter and you were talking about doing more work with oil, so are you working with oil now, and what’s the relationship between the two for you?

LS: I definitely work more with acrylic. It’s funny that earlier you said working with acrylic is hard – I think working with oil is hard! It’s just whatever you do or don’t do – like, I can drive a car but I’m sure racing one is really hard (that’s definitely not something I want to do). And I just think it’s what you want out of your paintings or your temperament. You know how some people say they have a fear of commitment? I think I have a fear of non-commitment, so when I started working in oil again recently, just the ability to change your mind and go over it – I have so many bad, terrible, mushy oil paintings. And with the acrylic I’m locked in and it has it’s own problems, but I think it can be exciting, you just have to work with what you’ve got, building your own situation that’s working well, and that’s it. So the speed and the inability to change has been good. And then I also like that I’m painting landscapes that have a natural topographical element to them but are also definitely being compromised by or changed by the built environment, and so using a plastic or artificial paint material seems good for that. Either one is harder depending on what you do. I’ve worked now solidly for ten years, so I’m pretty knowledgeable about acrylic and how to make it ooky-gooky like oil, but even in the last show there were a couple moments where I just couldn’t get the lushness, and so I did do some delicious oil gum drops on top, which I’m always a little leery of doing, because you can see when people do that. I don’t know why that’s a problem or not, I guess as a painter you are tempted to pick it apart and see how it’s put together, and it stops being a painting and you just want to find which is which. You probably do that, I do that! And then stop thinking about the painting as a whole. But I had a painting that had corn in it, so I guess if I could do that, I could do anything with oil and acrylic too.

Rotting Jack-O, 2012, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

AG: What is your interest in working with imagery from post-industrial American landscapes and towns? It looks like you’ve been working with that for a long time, American industrial and commercial things in the landscape, a push-pull between the two in the short history of this country, I think it’s really interesting territory. I’m curious about your relationship to it and why are you interested in depicting it.

LS: I don’t know that it’s the industrial landscape, I think it’s more the commercial landscape. I think of industrial as factories, which I’ve done and some office parks, but my interest in and headway into that was when I did paintings of the industrial landscape in China for a couple years and how that related to our industrial landscape and our consumer society here. So I think the emphasis has been more of the commercialized landscape, the built environment. My interest came from growing up in the suburbs and seeing and feeling the emptiness and problems with the way that the landscape is structured through highways and streets and cars and big box stores. The first paintings I did outside of grad school were dealing with that and I've been dealing with that more or less over the last few years. And I think those spaces reflect a lot about how we organize ourselves and how we move around and how we value or don't value the landscape itself. And also exploring different ways to use landscapes as entry points to make paintings, whether that's the desert or oceanside or expansive Midwest. Not as much urban landscape, maybe because it's harder for me to paint buildings that don't look totally weird, or maybe being from the Midwest and being used to more open spaces, not urban spaces.

AG: You were talking about working from observation on site, but I thought I also read somewhere that you were working from some images from the internet, so do you work from a combination of observation, found images, photographs, imaginative stuff, and what role does memory have in that? Does experiencing something and then having your own experience in the studio add something to it?

LS: Obviously memory and imagination are both a part of it – there are no faithful photographic renderings in the paintings, not that photographs are faithful either, but there's obviously a lot of interpretation and exaggeration in the work. So for example the drawings that I'm doing right now, the ones that are from here are done on location. I did them on location or I drew them in the studio right when I got back that day, so even if it was from memory it was very close to the experience. Then the drawings of the trees in St Louis are from photographs that my parents took with an iPhone, plus memory and kind of making it up even more than I do in other circumstances. So it's definitely kind of a big soup of all of those things. I’ll find images on the internet if it’s something that I can't really remember and I need to look up something again, but it's not just working from a picture online and then making a painting. Plenty of people do that, it's fine, but for me it's just a part of the process I guess. Lots of input, lots of output.

AG: You were talking about working with ceramics – I saw in your show last year at CRG, you showed sculpture and ceramic work along with the paintings. Is that the first time you were working with the medium? What made you want to do that and how do you see them in relation to your paintings?

LS: Sculpture – that's what they are. I have other ideas of things to do in ceramics but I haven't done anything else except that. It just seemed like it had to be that way, so I had to make it in ceramics. And I didn't even know what they were in relation to the paintings until I saw them in the gallery, because in the studio there's so much dissonant 2-D and 3-D information. They became so much more figurative in the gallery. They became these characters. But I liked that, and I was able to take some of the figurative information out of the paintings and put them into the ceramics sort of subconsciously. So I think some of those paintings were a little more open than other paintings of mine – open space-wise and fewer details, which I liked. You were asking about oil before. I kind of got a little dead-ended with acrylic, so I started using oil. And then that was also not working out, so then I tried something else. I just started working with ceramics and I didn’t really know if it was going to go anywhere. It took a year and a half to get that work together for the show. This is a good example of a reason to visit a location and what can happen. It was in response to cactus farms that I visited in Arizona – the night that we got there was a once in five-year cold snap. The growth in the cacti is in the tips, so in all of the nurseries the farmers everywhere were running around all night long putting Styrofoam cups on all of the tips of the cacti. You can’t wrap a cactus in a sweater obviously, but the cups can save them. So we got to this farm and I was wondering why every cactus, thousands and thousands of cactus in every direction, had Styrofoam cups on the tips. And that was only because the once in five-year temperature drop happened when we were there. I tried to make it into a painting and it just wasn’t working, and then I realized that each of these is like a sculptural object with the Styrofoam cup on them and that could be an interesting way to go about it. So I built a cactus garden based on that. That needed to happen and it was a very clear reason. I’ve thought of other things to be made out of ceramics. I like some of the ideas but nothing has clicked in the way that did.

Slumped Cactus, 2014, glazed ceramic, plywood, sand, agate spikes, 41 x 16 x 14 in. Courtesy the artist.

AG: It's interesting when the subject itself drives the decision-making, and you just come to that realization that it doesn't want to be two-dimensional, it wants to be three-dimensional. And it only needs to be one or maybe a few instead of a whole farm or group of repeated images. It's not always your decision – this thing itself knows it would be articulated better in another form, that's interesting.

LS: It was fun. I recommend it. The modular aspect I liked, I'd make a top and bottom, and I wouldn't like how they worked, so I would switch them with other ones, and in painting...

AG: You can't do that as well in painting!

LS: You can, but I'm not cutting my canvas in half and attaching it to another canvas. And it was so great to be able to move things around physically. And to be able to change the color, it needed to be pink stripes instead of green dots and then re-glazing it.

Cacti Display, 2014, ceramic, found materials, porcupine quills and semi-precious stones, 57 x 46 x 58 in (detail). Courtesy the artist.

AG: I wonder how that would then inform the paintings, having had that physical and spatial ability to move stuff around, you might have a different kind of sensibility. You might be able to see the limitations of painting in a different way.

LS: Yeah, since that show I did a couple small paintings that I liked, but I've basically been working in paper where I have been able to cut the paper or just scrap it and not feel devastated in the way that painting can really hurt your feelings. So I hadn't even thought of that, although painting has been feeling kind of heavy lately, I haven't quite gotten back into it, for whatever reasons. In some ways you would think paper would be the least like sculpture.

AG: I could see that though, it's so much more immediate and you can change things around, even if it's a large-scale drawing, it's more changeable. Painting is so permanent, it's such an investment, it's a heavily loaded object, it's historical, and you're investing so much time and material. And with work on paper it is just a piece of paper, you can always throw it away or turn it into something else. Crumble it up and then it's an object, even.

When you were working on the Sock City series, you were focusing on the Chinese industrial landscape. I’m wondering how you resolved the issue of being a Western person going to do that work in an Eastern country – how did you deal with the history of colonialism when you're taking your impressions away and bringing it back to this country, and then dealing with that in a painting context? How do you resolve the history of going to the strange foreign lands and making images of their things and Americanizing them?

Crop Dusters, 2013, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 70 x 54 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

LS: When I work on bodies of work I get very clear about what I want to do and I have to do it. I was very curious about the post-industrial landscape here in this country and then seeing where the industrial landscape is and of course practically everything you touch and own is made in China, or at least some aspect of it. So of course, I was like this is maybe a really bad idea, but I'm going to go anyway, I'm going to go and just see what happens, and I'll make work or not. And then I made the work, and I thought about a lot of that – orientalism and colonialism. And then even to make the paintings, how to make them or not make them anthropological, another aspect of how Western and other cultures interact. And I didn't really know and I just did it, and I felt like I took it seriously, and then put the work out in the world and I felt like it was received in a respectful and intriguing way too. All of those things that you brought up I didn't ignore. I was totally aware of them. I thought through them. I felt that this is such a big part of our world –this exchange of commodities. So it's not like it's reverse colonialism. But again it's like this completely absurd exchange of objects between China and the entire world. There's this very historically significant exchange happening, and I felt like it couldn't be overlooked, no matter where I was coming from and how I was looking at it. I'm sure some people are critical of that – even taking that on. I would say that the paintings are of single-industry cities in China from my perspective. I'm not a journalist, so it's obviously very subjective. But I was curious enough to go there twice and think about it and make work about it.

AG: Because you're working with very traditional forms in the paintings –landscape and architecture –what do you think are the possibilities today for that kind of figurative painting?

LS: I'm thinking about that a lot. I mean on some level the landscape is perpetually changing and so is architecture and so is human movement. At the time that I was working on those paintings in China, it was the world's largest migration from rural to urban in human history. I don't know what the statistic is on that now, because in the last few years between the times I went, the migration was reversing because of the economic crash. So it will happen again in some other form. No matter what happens with technology and styles, people are going to keep moving around and keep building things and it's going to reflect our values. That always changes and what does it mean in painting? And also if you've got to paint, you've got to find something to paint, I think. Those things are all good subjects for books and movies too and people do it well, but I don't know how I would approach it that way.

Sad Tomatoes, 2013, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in. Photo by Tim Davis and Pete Mauney, courtesy the artist.

AG: I've had the pleasure of interviewing several established female artists such as yourself. A peer of mine, another young woman artist/painter, mentioned to me that I haven't addressed or asked the question of an established female painter who has been able to manage a family at the same time as their career and a continuing studio practice. So I'd like to ask you about that – how do you manage it all? Do you feel like it's enriched your life, do you feel like it takes away from your practice?

LS: I'm happy you're asking this question, even though it's the question you're not supposed to ask! It's almost this anti-feminist question – no one would ask a male artist that. But it's kind of all I think about, because I have one kid and I teach, and I'm an artist, and I'm married, and I have a social life. So it's like five enormous bubbles of energy that I float in. I think also in terms of feminism we're in this kind of complicated super-mom world, you're supposed to do it all –cook your own food, make the amazing playhouse, and have a job and a great career, and toned thighs. But then we can't talk about it. So I do feel like it's hard to do it all. And I feel like I can't do it all at the same time but I just might pop one or two of those bubbles. So our kid is two, and yes it's enhanced my life amazingly and he's amazing. And I did have a show when he was a year and a half old, and I did it, but it was really hard. And basically six months after that I had no energy to do anything creative. So you've got to figure it out. He's two and I’ve already had a big show, so I don't know what that means for the whole career trajectory yet, but I also think someone shouldn't tell you to have a kid or not, you should do what you want. I think both children and careers are fickle. And if you want to do it, have a kid or a career or both, you've just got to do it, but they both take a lot of time and energy. That is no joke! It's hard but not like in a pushing a rock up a mountain kind of way, although maybe pushing a small rock up a mountain, but it's a lot to manage.

AG: In a way I feel like it's not fair for your privacy to ask that kind of question, but I think if you look historically ,for example big deal male painters like Guston, they had kids and then didn’t worry about it because the wife is understood to be the primary caretaker and does everything and [she] isn't an artist and it's not his problem anymore. It's not like that for most women. Especially if both parents are artists, it's not easy. You don't have the straightforward caretaker type who's just going to do all the work, and you can do your own thing. And I think even now, the female role is that that is expected. It's great to have these examples of someone like you who's making it work and I think younger women starting out need to see this being talked about and hear what you have to say. And because it's amazing that you can handle it, and if you can do it, maybe we can too.

LS: Thanks, that's nice to hear. It doesn't work everyday, but without kids doesn't work everyday either. I mean, I think I had more unhappy days before him where I spent a certain amount of time dragging my feet. And now it's just more running around than that. And not that I have to be a big advocate for men's rights either, but I think that the expectation of fathers is different today too. I think a Philip Guston parenting approach right now as a dude would be disdained. That would not be pretty either! I mean, he could still be a famous artist, but I think it's hard for men to not take an active role with their kids and just smoke and hang out with Philip Roth and make paintings either. You can't get away with that anymore. That's not to say that women don’t have to carry a lot of what having a kid is in many regards too. We don't have a nanny but we do have family and babysitters. It's a lot easier to manage it upstate than the city family scenario. There is that difference, but I have lots of incredible artist friends in the city who have kids too, so it can be done.

AG: What advice would you give a young painter just starting out today?

LS: Because I teach, one big difference is this phenomenal debt that students leave school with, and I have a hard time with that as a teacher. This college debt is a new thing that needs to be managed in a bigger way. So that requires much more monthly income to pay back. I tried to always get as high of a paying job as I could with as few hours, so my first year out of college was working at an insurance company, where like twenty years ago I made like twenty dollars an hour –which was pretty good– and I worked twenty hours a week so I could work in my studio. Other friends worked at hipster coffee shops and that was cool too, but then they had to do that for fifty hours a week. I think essential elements outside of the economic part are having a studio and making work and to keep cultivating a group of artists around you to stay in dialogue with. So if that's graduating in the city and keeping up with those pals to have crit groups, or moving to other cities and making a new team. I think that wherever you are, that is essential and you've got to keep working. You've got to keep your mind in it and be excited about what you're doing.

AG: When I read your Art21 interview you said you wanted to be asked what you're reading, so what are you reading?

LS: Well, I'm slowly reading “Stuffed and Starved,” a book by Raj Patel about food scarcity and abundance in America and India and internationally. But I can only read nonfiction for so long and then I start to wander, so the book I want to read next is the new book by David Mitchell, the author of “Cloud Atlas”. So that's what I'm going to buy at the bookstore this week –I'm resisting purchasing it on Amazon!

Lisa Sanditz lives and works in Tivoli, NY. Her new tree drawings will be on view in a two-person show opening December 5th and on view through February 21st at Duet in St Louis, Missouri.